By Annie Hyung

As I read the syllabus for my first in-person Bienen School of Music ensemble in a full year, I was struck by the format description for our first concert of spring quarter: live and remote.

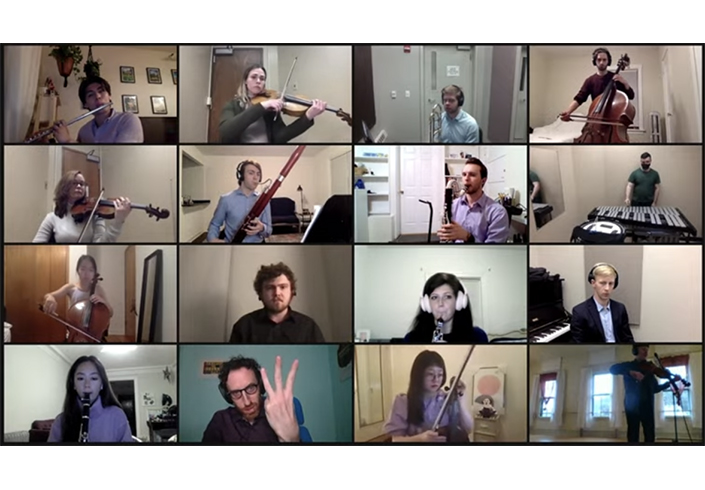

Using Zoom in conjunction with Cleanfeed, a separate platform with higher audio quality and minimal sound distortion, I spent four weeks rehearsing with a small ensemble of my peers online in real time. Working in this format piqued my curiosity to learn more about the logistics required to develop and implement a live remote rehearsal and performance space.

Alan Pierson, co-director of the Contemporary Music Ensemble and conductor and artistic director of award-winning contemporary ensemble Alarm Will Sound, shared more information about the thought process and gradual stages that preceded the live remote platform we currently utilize. Pierson immediately acknowledged many of the difficulties that accompany remote collaboration, admitting that even in Alarm Will Sound, “There isn’t a sound engineer or video director, or even a production manager. It’s really on each of the players to figure out their own set-up.”

When the pandemic first began, Alarm Will Sound engaged in click track-dependent ensemble playing, which remains the most typical method of remote collaboration. In the click track system, each musician is responsible for recording their own individual parts separately while listening to a common metronome track to ensure rhythmic accuracy. However, Pierson remarked that “It was amazing how fast that aged. By May, it no longer felt like an interesting thing to do for audiences. The players felt very disconnected. This uncharitable, unsocial experience quickly became normalized, and it was hard for a lot of people.”

The lack of a core social component of music-making—the emotional catharsis of feeling and moving together in an artistic body—inspired Alarm Will Sound to adapt works by living composers to play in real time in a virtual medium. Working in conjunction with composers allowed musicians to engage in what Pierson calls “a really meaningful artistic experience,” with added artistic guidance to navigate the quirks of an internet ensemble.

Pierson’s experiences working with Alarm Will Sound further inspired his creative search for ways to present more diverse performance opportunities to Bienen students, specifically in receiving direct coachings and feedback from contemporary composers over Zoom. As a student, it was an incredible opportunity to be able to communicate one-on-one with composers from across the world, to ask questions about the optimal ways to play their music, and to share the difficulties and triumphs of adapting to a virtual concert space.

There have been some silver linings of remote performance: one is a newfound capability we have as musicians to perform in front of cameras from our home spaces. “Being able to see musicians directly on camera makes for an interesting experience, and there’s a lot that can happen acoustically, because microphones and cameras become windows for direct connection with audiences,” says Pierson. Benefits of this technology-oriented world have now collided with the traditional acoustic concert hall, and Pierson hopes musicians will be able to learn from this previously foreign environment and integrate some facets of virtual communication into future, more traditional performances.

In my own live remote playing, there initially was a huge learning curve; I had never before needed to anticipate others’ sound in order to make up for inevitable internet latency. It took several days to become accustomed to locating certain musicians or even Pierson, our conductor, on my laptop screen. Playing remotely requires a different degree of faith in my own playing, partially due to wearing earbuds that obscure my own sound, and certainly in others’ playing as well, as we attempt to sync up cues that often do not line up to our own ears.

Despite these initial obstacles, I found myself relaxing into this rhythm of music and performance. Even from a distance, I was able to share a sense of unity and collaboration with peer musicians, and it was clear that every individual was entirely focused on the creation of an artistic product, no matter how strange and imperfect.

No one denies that there are still many challenging components within virtual ensemble work; it is not likely to completely fill the void of in-person collaboration. Despite this, it has revealed an expanded potential for experimentation with different platforms and opportunities for more direct interaction between performer and audience.

Through this experience, I was able to let go of a fixation on perfection, and instead embrace the internet latency and delay that made working together unpredictable. I realized that spontaneity can become a part of the music itself, was forced to analyze others’ sounds and cues more intently than before, and deeply appreciated my fellow musicians’ efforts toward crafting an artistic product. Many of the lessons I learned through live remote performance are ones I will carry back to the concert hall.

My remote live performance experience with CME proved to be fulfilling and shockingly communicative, and it serves as hopeful foreshadowing of classical music’s continuous ability to evolve.

Annie Hyung is an undergraduate cello performance major at the Bienen School of Music.

On Friday, May 21, at 7:30 p.m. the Contemporary Music Ensemble will present its final concert of the season. Conducted by CME co-director Ben Bolter, the performance will be streamed live.