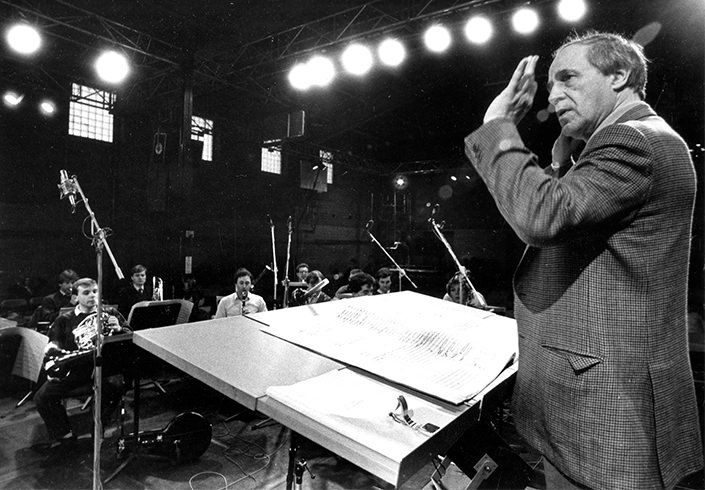

French composer and conductor Pierre Boulez, who died January 5 at age 90, visited Northwestern several times as a guest artist of the music school, beginning in the mid-1980s. For those who witnessed these visits, the memories remain vivid.

In 1986, 17 years after he had last appeared in Chicago, Boulez came to Evanston for a February 20 concert at Northwestern’s Patten Gymnasium. He had given a talk to Northwestern students the previous night. The concert was the Chicago-area debut of Boulez’s world-renowned Ensemble InterContemporain.

Bernard Dobroski, professor of music education and former School of Music dean, recalls that Patten Gymnasium had to be closed for a week before the performance to allow Boulez and his ensemble to rehearse. Despite blizzard-like conditions the night of the concert, people lined up to get in, and the gymnasium reached full capacity, with the audience arranged in a circle around the performers.

The concert began with Boulez’s Dialogue de l’Ombre Double for clarinet and electronic tape, written for Luciano Berio’s 60th birthday. The highlight of the evening followed: the Midwest premiere of Répons, a 45-minute work for 24 musicians, 6 solo instruments, and a 4X digital processor. In his Chicago Tribune review, John von Rhein called the performance “provocative and appealing, and it was in that adventuresome spirit that the attentive audience embraced the event.”

Richard Ashley, associate professor of music theory and cognition, was in his first year on the Northwestern music faculty. “The hammer stroke of the first big sonority of Répons, accompanied by a sudden blaze of lighting in the darkened hollow of Patten Gymnasium, was one of the most unforgettable musical gestures I have ever experienced,” recalls Ashley.

Victor Yampolsky, professor of conducting and ensembles, says that Répons demonstrated Boulez’s “phenomenal mind of invention. The combination of real sound with electronic sound—always interacting with each other—was fantastic and completely enveloped our ears. But the other interesting feature that struck me was the intervals, timbres, colors, and harmonies—it was all unmistakably French music. He was still a French composer.”

Boulez wrote Répons to be performed in a space with the conductor and chamber musicians in the middle, surrounded by the audience—allowing the reverberating sounds to wash over the listeners from all directions. Patten Gymnasium fit the bill, one reason for the Evanston performance. Another was Boulez’s friendship with Northwestern clarinet professor Robert Marcellus, whom he had conducted when Marcellus was the Cleveland Orchestra’s principal clarinetist.

Thanks to appointments with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra—first as principal guest conductor and later as conductor emeritus—Boulez maintained a close relationship with Northwestern’s nearby music school. In 1993, while in the area for a month-long CSO residency, Boulez brought the Ensemble InterContemporain to Pick-Staiger Concert Hall for its only Midwest performance that year. The November 14 concert was declared “the new-music event of the fall season” in a Chicago Reader preview, which called Boulez “arguably the most empathetic interpreter of new music.”

Ashley says Boulez’s skill as musical coach and conductor was on display throughout the Ensemble InterContemporain’s 1993 residency. “Whether gently coaxing a fluent and expressive performance of a solo clarinet work from an understandably intimidated student, or guiding the ensemble through nuances of Ligeti’s Piano Concerto, his ability to connect the score and the players through his musical intentions was masterful,” says Ashley.

Dobroski adds that Boulez was very gracious with music students and faculty during his visits. “He was approachable. Our students left thinking that not only had they gotten to know him as a musician, composer, and conductor, but they had also glimpsed into his humanity.”

Dobroski recalls 2002 as the last year Boulez visited Northwestern’s Evanston campus. He was in Chicago that December conducting the CSO in the premiere of In My Sky at Twilight by Augusta Read Thomas, then a School of Music faculty member.

Associate professor Hans Thomalla, director of the Institute for New Music, calls Boulez one of most important figures in new music since World War II. “Boulez was an institution builder without comparison, creating spaces for composers, performers, and theorists to explore and expand the field,” says Thomalla. “And he was unique in his ability to maintain a place for new music—always in danger of disappearing at the fringe of society—in the center of classical music and of culture at large.”